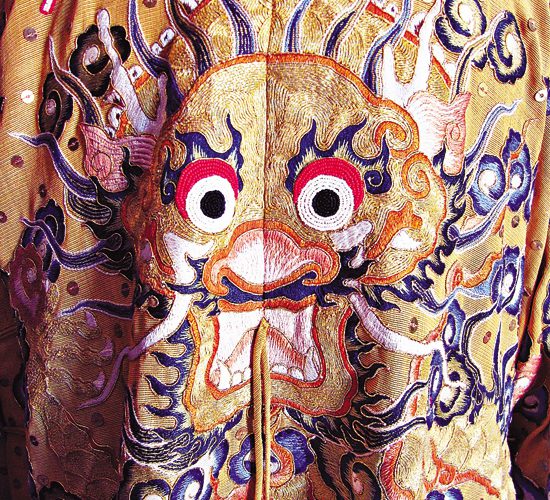

Left: a ?ông C?u dragon-embroidered garment. Photo: Le Viet

Right: phoenix-prowed shoes from ?ông C?u. Photo: An Thanh Dat

Vietnam Heritage, July-August 2011 — Th??ng Tín District, Hanoi, is known for villages that embroider, but while most neighbouring villages tend to embroider pictures, ?ông C?u village, D?ng Ti?n Commune, has an embroidery tradition of serving festivals and worship. It specialises in ceremonial goods such as the tán l?ng (parasol), nón th? (ceremonial hat, as hung in pagodas and temples), áo ng? (the dress a medium wears when going into a trance) and hia hài (ceremonial shoes) vividly embroidered with dragons and phoenixes. ?ông C?u and has been dubbed ‘the village of dragons and phoenixs’.

Lê Công Hành (1606-1661) is regarded as the father of Vietnamese embroidery. He went to China and studied embroidery and taught the villages of Qu?t ??ng, T? Vân and ?ông C?u. Each has a shrine to Lê Công Hành. ?ông C?u’s embroidery occupation began in the 17th century, according to One Thousand Years of Thang Long Culture (Culture and Information Publishing House, in cooperation with Vietnam Economic Times, Hanoi, 2007).

Mr Thuan, 70, an artisan who makes ceremonial clothes, said, ‘Once, this craft was mainly to serve formal activities at pagodas and festivals. Some excellent embroiderers were selected for royal workshops, to make royal attire. In the late 19th century, when feudal dynasties collapsed and religion was limited, ?ông C?u villagers were less involved in the craft. However, we have come back to our ancestors’ craft for the past ten years because we wish to preserve it as our village’s own treasure. Another reason is that demand for ceremonial items has been increasing, thanks to open policies toward religion, restoration of festivals and more construction of pagodas and temples.’

Mr Thuan said the village did its best business in spring, which is festival time for Vietnamese. Most families in ?ông C?u go into the craft. Children aged ten are taught to use a needle and embroider basic dragons. There are a hundred workshops in the village, each specialising in one product.

The Vietnamese resurrect and preserve rituals related to gods and saints, preparing lists of items connected with ancient and divine scenes. Dragons and phoenixes appear on all products. Mr Thuan said, ‘The Vietnamese are called ‘children of dragons and grandchildren of gods’. The dragon and the phoenix are a harmonious couple, symbolising power and beauty in the spiritual part of the Vietnamese mind …’

Áo ng? is the dress a ‘bà ??ng’ (medium) wears when going into a trance. Mr L?u, boss of a vestment workshop, said, ‘This is a saint’s outfit. A saint descends [from heaven] with his own costume. So, the medium has to change into many different vestments in a ritual. My workshop received an order for 15 brocade outfits from one customer a month ago. A brocade outfit costs VND2-3 million.’

Ms An, an embroiderer aged 25, said, ‘It often takes me 20 days to complete a brocade outfit.’

The process includes designing, printing,

selecting materials and colours, embroidering and tailoring and accords with tradition.

Mr Lau said ‘Although a machine can manufacture quickly, manual embroidery remains more effective in creating a sharp appearance.’ He added, ‘A skilled worker has to spend three years practising with the needle, because many difficult techniques are big challenges. An embroiderer should sit four to nine hours to make a dragon design with its complete soul. More importantly, the ceremonial vestments need to be thorough because they are worn on holy occasions. My workshop recently produced six outfits for the H??ng Pagoda Festival. We both met the order on time and absolutely avoided mistakes.’

The nón th?, ‘ceremonial hat’, is hung in pagodas and temples. Mr Au, 45, who makes ‘nón th?,’ said, ‘A ceremonial hat is decorated colourfully, to welcome gods from heaven.’ All members of Mr Au’s family participate in making. Mrs Thanh, his wife, embroiders designs on cloth, then he ‘b?i gi?y,’ pastes the embroidered cloth on to paper. Their two children dry the hat in the yard, ‘g?n c?t’ (give embroidery a wooden frame) and attach tassels, flowers and the head of a phoenix, made of paper.

Hia hài, ceremonial shoes, take time. Craftsman Mr Lan said, ‘As in the vestment-making, it is important to plait thickly to get a well-fed dragon-body, which symbolises wealth and happiness.’

Women do agricultural work as well as ‘dragon and phoenix’. Children go to school.

In all Vietnam, there are 8,000 festivals, and the ?ông C?u craftspeople can supply any of them. Mr Lan said, ‘Ph? Gi?y festival orders a large number of shoes from us annually. A customer even had a VND30-million order for costumes for ‘h?u ??ng,’ trance rituals.’

?ông C?u is one of only a few villages in Vietnam that produce the ceremonial requisites, and so its ‘dragon and phoenix’ products travel far and wide.