(No.3, Vol.2 Mar 2012 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

Hue was the capital of the last dynasty of feudal Vietnam. The August Revolution of 1945, led by the Vietnamese Communist Party, ended the feudal system, which had dominated for thousands of years.

On the afternoon of 30 August, 1945, in Hue, before dozens of thousands, Emperor Bao Dai abdicated. After reading the speech, according to Tran Huy Lieu’s memoir, Bao Dai ‘raised the long, gem-studded sword, then a square seal, over his head. I [Tran Huy Lieu], as the representative of the provisional government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam [predecessor of the current Socialist Republic of Vietnam], took over the symbolic objects of the feudal regime. Besides the seal and the sword, there was a set of chessmen and some other valuable knick-knacks in a brocade bag.’

That day, the delegation of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam took the national seal and sword to Hanoi for Independence Day on 2 September, according to the memoir.

In October 1996, on a research trip to France, I met Madam Bui Mong Diep, Bao Dai’s secondary wife, and had a long talk with her. I [tape-]recorded the talk. She told me the national seal and sword King Bao Dai had surrendered to the government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam had ended up in the hands of the French, who, in 1952, had returned them to Bao Dai. In 1953, Bao Dai had designated Madam Mong Diep to take the seal and sword and other valuables to [former] Queen Nam Phuong in France. In 1963, when [former] Queen Nam Phuong died, the seal and sword had gone to Crown Prince Bao Long. And it was said that Bao Long had lately sold the sword.

Some imperial seals of the Nguyen dynasty were of jade and some of gold. Both kinds were square. In an article ‘Imperial seals in the Nguyen Dynasty’ in the collection ‘The Socio-Cultural Issues in the Nguyen Dynasty’, published by Ho Chi Minh City Institute of Social Sciences, Vietnam History Museum in Ho Chi Minh City and Social Sciences Publisher, in 1992, Tran Viet Ngac and Van Dinh Hy wrote, ‘Emperor Gia Long had six gold seals. Emperor Minh Mang had another eight made. So in total the two monarchs had 14 different seals for different purposes, for example, edicts, decrees, or certificates of merit, etc.’

Paul Boudet wrote in the book The Archive of the Emperors of Annam and History of Vietnam (published by Societé de Géographie de Hanoi, 1962) that he had, with permission from Emperor Bao Dai, been shown seals of Nguyen monarchs stored in Can Thanh Palace in Hue. Boudet said the Nguyen monarchs had 46 gold and jade seals in all, most of them made after Emperor Minh Mang’s reign.

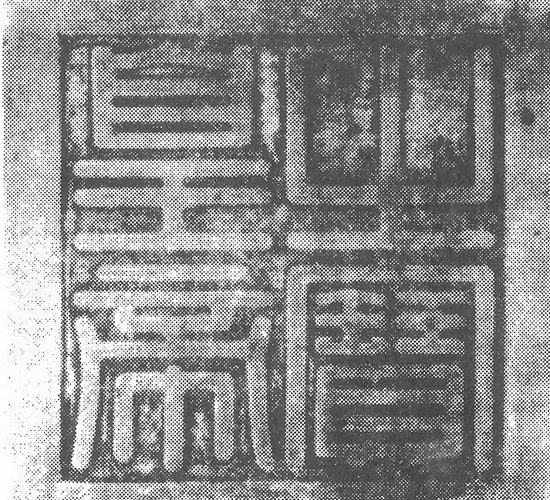

The imprint of the seal ‘The Emperor’s Treasure’, from a black-and-white photograph in Le Van Lan’s the Last Seal of a Vietnamese Emperor, Làng Publishing House, USA, 2001. The photo is provided by Nguyen Dac Xuan

According to the book, the storage of the jade and gold seals, tigerhead-shaped insignia, and gold books was classified top secret, not to be seen without the Emperor’s permission. According to the book, every year, before the Lunar New Year, on the Emperor’s order, the mandarins in charge of imperial records held a trunk-opening ceremony to inventory the precious items and clean them with scented water (water boiled with fragrant flowers) and dry them with a piece of red cloth before putting them back in their places, according to a Chinese-language plan.

At the handing-over ceremony on 30 August, 1945, Pham Khac Hoe, head of the cabinet of Emperor Bao Dai, said in a book with a title referring to the transition from dynastic to Communist rule, published by Thuan Hoa Hue Publishing House, 1987, that he had supervised an inventory and had a list rewritten in Vietnamese.

Mr Hoe later said all the treasures [including the sword and seal appearing in the handing-over ceremony of 30 August, 1945] had been turned over to Le Van Hien, representative of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam provisional revolutionary government. Mr Hoe said the government had then shipped them to Hanoi.

Mr Hoe said the personal possessions of Bao Dai, his wife Queen Nam Phuong and the Queen Mother Tu Cung had been moved to An Dinh Palace [in Hue] and had remained the possessions of Bao Dai, his wife Queen Nam Phuong and the Queen Mother Tu Cung.

Professor Ha Van Tan wrote in the Vietnamese Archaeology of January 1996 that ‘For the time being, the National Museum of Vietnamese History houses some of the golden books from Hue [taken over from the Nguyen Dynasty]’.

Madam Bui Mong Diep told me that in 1946 French troops, digging positions in Hanoi, had found a steel container holding a seal and a sword, the latter painted black and broken in two.

Doctor-lawyer Nguyen Huu Nhon, in an article in Ng??i Lao ??ng of 5 September, 1997, said the seal and sword handed over on 30 August, 1945, had been found on 28 February, 1952, in Nghia Do Village, in the suburbs of Hanoi, and by French troops. He said the soldiers had broken the sword and the seal while digging. In my view, Nhon did not source his information sufficiently. According to other sources, the French unearthed a seal and sword much earlier than 28 February, 1952.

Jacques Massu and Julien Fonde, in L’aventure Viet-minh, Plon, 1980, said a ceremony of returning of a seal and a sword to the former Emperor’s family had taken place on 8 March, 1952.

Bao Dai did not apparently attend and his mother and his secondary wife, Mong Diep, received the items on his behalf.

Madam Mong Diep told me in 1966 when I met her in France, ‘Bao Dai was on a vacation abroad. They called me when I was in Buon Ma Thuot [in the Central Highlands]. I had never seen those precious things, so I am not sure they were the actual seal and sword which Bao Dai had handed to Tran Huy Lieu in 1945. I invited the Queen Mother Tu Cung from Hue to fly to Buon Ma Thuot to join me.’

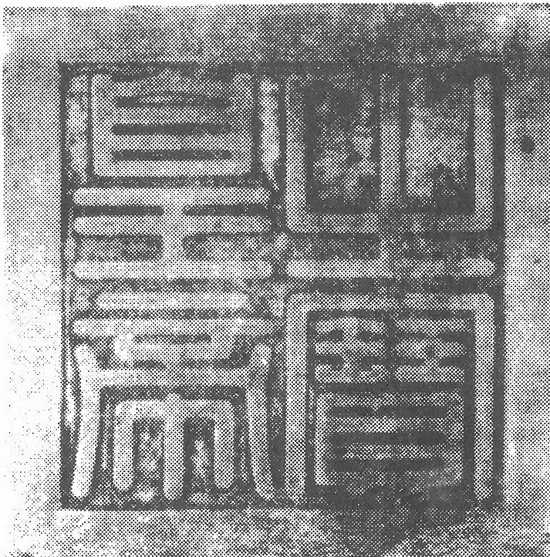

The Seal The Emperor s Treasure , provided by Nguyen Dac Xuan from the Internet

Madam Mong Diep said, ‘At the ceremony, Queen Mother Tu Cung requested that the seal and sword be placed on an altar at Buon Ma Thuot airport and covered with a piece of red cloth. We had to kowtow to them before bringing them back home. Back in the palace, I had the seal and the sword washed, covered in a red cloth, and put on a table in the middle of the building. I had them heavily guarded round the clock.’

Madam Mong Diep said the Queen Mother had told her that in August, 1945, the seal and sword had been relinquished to save the life of the Emperor. They had returned out of the blue. When Bao Dai had come back she told him that for some unknown reason the seal and sword he had handed over to the delegation of Tran Huy Lieu had got into the hands of the French and lately they had called and returned them.

Madam Mong Diep said Bao Dai had walked over and ripped the red cloth off and mumbled, ‘Yes, there they are …’ and remarked on the weight of gold in front of him, ‘almost 13 kilograms’.

Madam Mong Diep said the abdicated Emperor had designated her in 1953 to bring the royal treasures to France to Queen Nam Phuong and Prince Bao Long.

Madam Mong Diep told me that after Queen Nam Phuong’s death, in 1963, the seal and sword had come into the possession of Prince Bao Long.

Madam Mong Diep told me in 1980 that Bao Dai had published the memoir The Dragon of Annam and had wanted to use the seal to create vignettes at the end of each chapter and Bao Long had refused him.

According to the book The Last Days of President Ngo Dinh Diem, by Hoang Ngoc Thanh and Than Thi Nhan Duc, published by Quang Vinh, Kim Loan and Quang Hieu in 2011 in California, Bao Long lodged the seal and sword with the Union des banques Européennes.

Madam Mong Diep told me Bao Dai had sued his son for the seal and sword. The court had determined that Bao Dai got the seal and Bao Long the sword.

Professor Thai Van Kiem, who was close to Bao Dai during his last years, owns pictures of Bao Dai sitting in front of a seal with a thoughtful look. Le Van Lan wrote in the Last Seal of a Vietnamese Emperor, published by Làng Publishing House, USA, 2001, that the seal before Bao Dai had been the actual one relinquished by and returned to Bao Dai.

Madam Bui Mong Diep told me in 1996, ‘I myself cleaned the seal and sword when Le Thanh Canh flew from Hanoi to Buon Ma Thuot to hand them to me. The sword was broken into two pieces. I had two trusted servants, Tu Lang and Thua Te, take it away to be mended . . . welded and . . . the joint polished. As for the gold seal, I weighed it myself: it weighed 12.9 kilograms. It had a dragon-shaped handle. The dragon was curling with its head raised; the sculpture was not very delicate. It had two red gemstones studded on the head; it looked more like a snake. I turned it upside down and saw four Chinese words on the bottom. A person who could read Chinese told me the words were “the Nguyen Dynasty’s treasure”. After having it washed and cleaned I had it soaked in ammonia; it took no time to sparkle.’

The Last Days of President Ngo Dinh Diem says the seal relinquished ceremonially weighed 6.9 kilograms. Tran Huy Lieu said in his memoir it weighed 7 kilograms. Pham Khac Hoe, head of Emperor Bao Dai’s Cabinet, who had advised abdication, wrote in the book cited earlier, ‘The gold national seal weighed 10 kilograms.’ Le Van Lan, based on his own research, asserted that the seal weighed more than 10 kilograms and was named ‘The Emperor’s Treasure’; it was square, 12 cm by 12 cm, with a base 2 cm thick. The handle was in a curling dragon’s shape. In the above-mentioned books of Tran Viet Ngac, Van Dinh Hy, and Paul Boudet, there was a seal named ‘The Emperor’s Treasure’. The seal was made 17 March, 1823, according to Nguyen Huu Nhon (mentioned above) and many other documents.

According to Le Van Lan’s abovementioned book, on the sword’s sheath there were inscriptions which read ‘In the year of Emperor Khai Dinh’s reign’. That means the word was forged in the period from 1916 to 1925. The blade was made of steel. On the sheath there was information about its gold content, 178 grams. It is not clear if the gold was melded into the steel or was used to make some part on the sheath or the hilt. The hilt was inlayed with gems.n

* Nguyen Dac Xuan is a researcher specialising in Hue

Bao Dai with the seal The Emperor s Treasure, in Le Van Lan s Last Seal of a Vietnamese Emperor,

in Le Van s Last Seal of s Vietnamese Emperor, Làng Publishing House, USA, 2001. The photos are provided by Nguyen Dac Xuan.