(No.10, Vol.4,Nov-Dec 2014 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

Betel and areca nut.

Photo: James Gordon

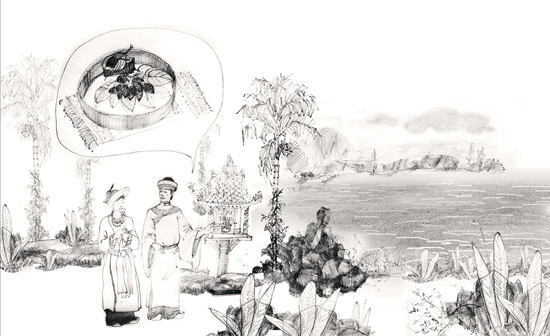

In ancient times lived the brothers Tan and Lang, who, although their ages were different, looked as alike as two peas in a pod. Their father was the tallest and biggest person in the region. He was rewarded by the Hung court, which bestowed on him the honorary name ‘Cao’ (tall). From then on, his family assumed the Chinese character ‘Cao’ for their genealogy.

As the brothers grew up, their parents passed away. The brothers then became more attached to one another than ever. Before their father had passed, he entrusted Tan to a Taoist from the Luu family. Tan studied with the Taoist, and Lang, unwilling to just stay at home, went to study alongside his brother. In the Luu household was a girl of the same age and social standing as the two brothers. Loving feelings for the girl sprouted up in both the brothers, but she gave her heart to the older brother. The Luu Taoist betrothed the girl to Tan. After they were married, the husband and wife went to a new home, where Lang lived together with them.

Since the day he married his wife, Tan continued to cherish his younger brother, but not as ardently as in the past. Lang felt lonesome and his heart was full of sadness and despondency.

One day, Lang and Tan went together to the terrace-fields until late in the night. Lang went home first. He had just stepped past the threshold when Tan’s wife came out running from her chamber and embraced him. Lang cried out. His sister-in-law’s mistaking him for her husband made them both feel ashamed. At the time of the incident, Tan had just stepped inside. From then on, Tan harboured jealously towards his brother. Tan’s jealousy accentuated his cold temperament towards Lang. Lang, feeling downhearted, indignant and ashamed, wanted to leave home.

One day in the dark early morning, Lang absconded from the house and travelled along a dirt trail. After several days on the road, Lang came across a large swift-flowing river. He was unable to get across the river, so he just sat down on the riverbank, held his head, and cried. Lang cried and wailed until even the birds that prey in the night could hear his sobs. By morning, Lang was little more than a spiritless corpse and thereupon, he turned to stone.

Tan waited and watched, but he didn’t see his brother anywhere. Tan was contrite, for he knew that his brother had taken off because he was resentful of him. Tan went searching for his brother without saying a word to his wife. After several days, Tan, too, arrived at the banks of the broad swift-flowing river. Without any means to get across, he followed along the river until he found his younger brother, who had turned to stone. Tan stood beside the stone and wept until only the burbling of the rushing water remained. Tan died and transformed into a tree that sprouted straight up towards the sky beside the stone.

Tan’s wife back home waited and waited, but her husband didn’t return, so she, too, left the house to look for him. The woman sat next to the tree and wept until her tears ran dry. She then died and turned into a vine that wound around the upward sprouting tree.

The Taoist and his wife waited for them, but they didn’t see the three of them return, so the Taoist and his wife split up to look for them. In front of the stone and the two plants, they erected a shrine. That was a shrine for the ‘congenial brothers and faithful husband and wife.’

One year there was a drought. All varieties of vegetation were withered and dry. Only the two plants that sprouted up next to the stone were still verdant. The Hung King, on a royal inspection tour, saw that it was odd and asked the villagers about it. Touched by the story, the king felt compelled to order someone to climb the tree, pick its fruit, and taste it. The flavour was acrid and unexceptional, but when chewed with the leaves of the vine an uncanny flavour came to the tip of the tongue. It was sweet, fragrant and pungent.

Betel and areca nut, which are necessary items in a wedding ceremony.

Photo: Kim Thanh

Suddenly, a courtier exclaimed, ‘Blood!’ Everyone stood aback in awe. When the king’s spittle was expectorated onto the stone, it turned blood red. The king ordered that they fetch all three of them so that he could chew them together. He felt a heated sensation as if inebriated in a bouquet of liqueur and his lips turned crimson red and he had a ruddy facial complexion. The king declared, ‘Indeed, this is quite extraordinary.’

Thereafter, the king decreed that everyone cultivate strains of the plants and stipulated that all conjugal couples must have those three things during their betrothal ceremonies in memory of the love between the aforementioned husband and wife. The legend of betel and areca nut thus came into being and constituted the beginnings of the Vietnamese custom of chewing betel.

We don’t know when the legend came to be or how long it has been veiled by the dusts of time, but its association with the Hung Kings allows us to believe that the tale of the betel and areca nut along with the custom of blackening the teeth by chewing betel came into existence during that era.

An early 20th-

century northern woman, teeth

blackened from chewing betel.

Photo: Pierre Dieulefits

Women with blackened teeth from

chewing betel, Bac Ninh Province, 2010.

Photos: Nguyen Anh Tuan

In many boat-coffin graves that date from the time of the Hung Kings and An Duong Vuong, archaeologists of ancient times found that the graves’ occupants blackened their teeth and were buried with betel leaves and areca nuts in their coffins. The graves have been determined to be those of ancient Vietnamese, as ancient anthropologists have specified anthropological indicators in them, while archaeologists have recognized purely Vietnamese elements in the manner of burial that is consonant with the riverine ways of farming inhabitants.

The custom of blackening the teeth by chewing betel seems to have ceased between the seventh to eighth centuries of the Common Era. It’s unclear whether archaeologists have not yet discovered traces of it or that that was just the reality. That period was the era of northern (Chinese) feudal assimilation, which may have caused the ancient Vietnamese of the region to be unable to resist conforming to Chinese ways in regards to the custom. I don’t believe in the successful assimilation by the foreign state very much, as in nearly every area, the ancient Vietnamese selectively adopted positive foreign elements while still retaining their original traditional character, which causes scholars to assert that it was precisely only because we Vietnamese resisted the Han and Tang Chinese that we are who we are.

Coming to the Ly and Tran dynasties, the custom of chewing betel is illumined through the extremely rich collection of terra-cotta and porcelain spittoons. That time can be seen as the nascence of a system of Vietnamese spittoons, which developed all the way up to the August Revolution of 1945.

In the Le Dynasty, the custom of blackening the teeth by chewing betel existed prolifically and seems to have become a habit of the imperial family and the nobility, for in the tomb of Emperor Le Du Ton was found an embroidered bag for holding betel and areca nut, and the emperor had blackened teeth with a small proportion of gold in his hair. In many compounds from the tombs of officials were found material traces of the custom, demonstrating that not only women, but also men and not only the plebeian classes, but also the ranks of royalty, officials and nobility all used betel and areca nuts as a traditional Vietnamese custom.

As for later dynasties, especially the Nguyen, collections of imperial gold, silver and precious jewels present many gold and silver pestles and mortars that were used for grinding betel. Gold, jade, silver and bronze spittoons evince the rank and identities of those who used them. This is seen in the decorative designs of dragons, phoenixes, the four sacred creatures (dragon, unicorn, tortoise and phoenix) and the four noble plants (pine, chrysanthemum, bamboo and apricot) on the implements.

The custom of blackening the teeth by chewing betel became quite commonplace during the first decades of the twentieth-century. It entered into the lives of common folk through marriage ceremonies, funerals, ancestor remembrance days, and the adage ‘a mouthful of betel is the beginning of a conversation.’ The custom can be considered a thread that binds the community, village, and families. It is, moreover, the essential spirit of the people, which has been preserved for over 2,000 years, such that it, along with other cultural components, shaped the rich character of the Vietnamese people.

Today, the custom of blackening the teeth by chewing betel is already a thing of the past, yet it appears that worship rituals, betrothal ceremonies and marriages must all have the areca fruit and a platter of betel as a Vietnamese recollection of the distant past rather than as something of practical significance. That is the custom’s symbolic value in Vietnamese culture, which we come across everywhere, although few notice it, especially today’s youth.