(No.1, Vol.2, Jan 2012 Vietnam Heritage Magazine)

During the Ly Dynasty (1010-1225) and Tran Dynasty (1225-1400), Vietnam’s independence was safeguarded and strengthened, and the Vietnamese culture revived and developed. This period also saw the height of Buddhism in Vietnam. Several royal palaces and large Buddhist stupas were built.

Vietnamese ceramics flourished, expressing their vitality and confirming their identity while receiving and incorporating various elements from the Chinese, Cham, Khmer and Indian cultures. Archaeological finds have shown ceramic production centres of this period in Hanoi as well as in the present-day provinces of Hai Duong, Nam Dinh, Thanh Hoa and Ninh Binh. Ceramic wares were commonly used, from royalty to folk. Several glazed types appeared, with varied forms and decorative motifs. Many pieces attained high quality in terms of technique and aesthetics.

‘Ivory-white ceramics’ is a category given to pieces glazed in white, greyish white, grey-ivory or ivory-coloured ash (the most typical and basic glaze of Ly Dynasty ceramics). Forms include ewer, bowl, cup, vase, jar and lotus-petal dish. The most popular decorating motifs are the lotus-petal collar, lotus spray, Ly-style dragon, phoenix, lemon flower, stupa, wave, parallel lines and cloud stylized to a bodhi leaf.

Remarkable are two ewers with a lobed body, lotus-petal collar, dragon-head spout and parrot-form handle. Birds, including the Buddhist garuda and the parrot, are two favourite motifs in Ly ceramics.

Ly-Tran ewers have definitely Vietnamese shapes, not Chinese.

Very special is a lotus-petal dish or lotus pedestal decorated with a Ly-style dragon among vegetal motifs on the unglazed upper surface and a band of fairies on the supports.

A rare type is three joined cups with three phoenixes carved on joined covers. Perhaps this type was used in the Ly royal families.

Two greyish-white bricks, one circular and the other rectangular, are vestiges of Ly building. Both are decorated with carved Ly-style dragons, dancers, waves and lotus petals.

Celadon ceramics form another category. The celadon ware must have been produced very carefully. The clay must be made as clean as possible. The body must be smooth, dense and solid. The green glaze must be thick, transparent and glassy, like jade. However, different firing temperatures, atmospheres and glazes may have resulted in different tones, from greyish-yellow, lemon yellow, dark green to apple-green.

Ly-Tran celadons include mainly ewers, bowls, vases, stem cups, dishes, boxes, incense-burners, tureens, pots and spittoons. Each type has various decorations and shapes. Many pieces, including covered tureens (li?n), bowls, dishes and high stem cups, have shapes similar to Sung and Yuan celadon wares. At the same time, many pieces have Vietnamese shapes.

Like ivory-white ewers, celadon ewers have bulbous bodies, dragon-head spouts, parrot- or small-bird-shaped handles and lotus-petal collars and some have applied rosettes on the shoulder.

Celadon bowls and dishes have various shapes but similar decorative motifs. In the 11th – 13th century, pieces often have a slightly everted lip, curving wall and small footring. Some versions are V-shaped. In the 13th-14th century, pieces tend to reduce the body curving and widen the footring. Lotuses and chrysanthemums are a leitmotif, in various themes and arrangements.

Celadon stem cups have an everted mouth, curving wall, deep well and bamboo-shaped foot.

A tureen has a flat mouth, short neck, pregnant shoulder, tapered body and flat base. Its exterior is carved with an uneven lotus petal.

The late 14th and early 15th centuries saw the appearance of a kind of celadon dish with brown glaze as well as a kind of bowl with celadon glaze on the exterior and blue and white on the interior.

Pots glazed green or yellow form a third category. They often have a low-fired, white body (under the glaze). Many shapes and decorative motifs are similar to those on brown-pattern ware. Many examples have been found at the site of the ancient citadel of Thang Long, now Hanoi.

A notable object is a pillar-pedestal in the form of a gourd. To peoples in Vietnam and Southeast Asia, the gourd is a symbol of fecundity. Some elements of their traditional architectures, especially of pillars, pillar-pedestals and struts, are gourd-shaped.

Most interesting are thirteen human heads and one statuette of a woman with green or yellow glaze marks on the back. Their function and origin are still unclear, though in the National Museum of Vietnamese History they are noted as amulets. Their big eyes, headbands, headdresses and single or double chignons are reminiscent of the ceremonial statues of many minority groups in Central Vietnam and Indonesia. It is not impossible that these pieces are related to the Cham.

Brown-patterned and brown ceramics are a fourth group. Brown-patterned ceramics were produced from the 11th to the 15th centuries. They include all pieces decorated with: a/ brown inlaid patterns against an ivory glazed ground; b/ ivory inlaid patterns against a brown glazed ground; c/ unglazed patterns carved through brown glaze; d/ underglazed brown patterns and ivory glaze.

Of these, tall, cylindrical jars with either brown or ivory inlaid designs are highly regarded by scholars of Vietnamese ceramics for their unique decorative technique and distinctively Vietnamese motifs derived from the Dong Son artistic tradition. Most typical is the fragment of an unusual large jar, now in the National Museum of Vietnamese History, decorated with warriors, elephants and realistic lotus flowers. Two warriors are holding spears and shield in combat posture. Their thighs are tattooed with dragons. Tattooing was a popular during the Tran Dynasty for expressing Vietnamese totemism and martial spirit.

Many pieces reflect a Cham influence. One of the most notable examples is a pair of peach-form ewers, one incorporating Kinnara and the other Kinnari, the male and female haft-bird, haft-human singers for Indra, the Indian Rain God.

Buddhism was the most influential religion of the Ly-Tran times. Accordingly, the lotus is the most common motif on Ly-Tran brown-pattern ceramics, figuring in various forms: tiered petal pedestal; carved or molded lotus-petal collar on jars, inlaid lotus scrolls; inlaid lotus flowers and leaves repeated in panels; potted lotus spray and stylized lotus.

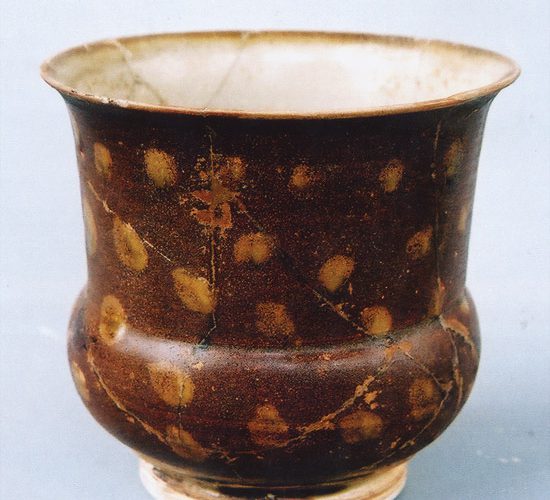

Brown ceramics include all pieces covered with brown glaze varying from dark to olive-brown.

Two human heads seem to be parts of statues. Their origin and function are still unknown. A statue of an elephant and its driver was made in the Tran period, when the elephant and its strong trunk were represented on many ceramic items, in some cases possibly as a symbol of the Vietnamese martial spirit.

Two ewers are decorated with a bird-print motif or chicken-foot decoration.

Architectural and art ceramics are a fifth category from the Ly-Tran period. Architectural and art ceramics consist of actual bricks, roof and floor tiles, ornamental roof sculptures, altar pedestals and models stupas.

Excavated sites at Lang Pagoda (Hung Yen), Chuong Son Stupa (Nam Dinh), Tuong Long Stupa (Hai Phong), Phat Tich Stupa (Bac Ninh) and especially at Thang Long’s ancient citadel, in Hanoi, have provided numerous examples.

The collection in National Museum of Vietnamese History, Hanoi, has three Ly stupa bricks. One is carved with two dragons flanking a central bodhi leaf in which there are two phoenixes. One is inscribed with the Han characters for ‘Produced in the fourth year of the Long Thuy Thai Binh reign’, equivalent to 1057. The third has three multi-storey stupas in relief.

The collection has two Tran stupa bricks. One is a fragment carved with a tiger among waves, the other is carved with a seven-storey tower surrounded by a band of circles.

Of special interest are animal sculptures including mandarin ducks and heads of dragons and phoenixes.

The mandarin duck has been found among architectural ornaments of the Dinh, Early Le, Ly and Tran Dynasties. The collection has two examples from the Ding-Early Le and Tran. This water-fowl is a splendid plumage. Either single or in pairs it is a symbol of felicity, similar to the phoenix. The mandarin duck was put on the roof ridge or the eave edge both magical (warding off evil spirits and protecting buildings from fire) and decorative purposes.

Sharing the same functions but also to symbol royalty, Buddhism or the occupant are the figures of the dragon, phoenix and bodhi leaves. The dragon especially represents a Tran military mandarin.

Most impressive are the dragon and phoenix head sculptures on the roof ridge. Their large sizes suggest the grandeur of Ly and Tran royal palaces. At that time, the dragon was a symbol of both the nation and the royalty. It was also related to the rain god.

It is possible that the phoenix head on the roof-ends of Ly and Tran buildings are also related to bird heads at the two gabled ends of a house incised on a Dong Son drum.

The collection has six square Ly or Tran floor tiles. Three Ly pieces are carved with dragons winding inside a circle, dragons inside a bodhi leaf and an eight-petal, blossoming lotus. Three Tran pieces are incised with different floral motifs.

Tran architectural ceramics share a liberal and realistic decorative style with other Tran wares.

* From 2,000 years of Vietnamese ceramics, published by National Museum of Vietnamese History, Hanoi, 2005

Above and opposite: Examples of a class of ceramics of the Ly-Tran period using a characteristic brown glaze. Photos: Nguyen Anh Tuan

Having covered, in the December 2011 edition, the millennium of Chinese domination, Vietnam Heritage continues its series on Vietnamese ceramics with the Ly and Tran Dynasties (11th – 14th centuries)