No 3, Vol.5, April – May 2015

Photo: Jonathan Bar-On

Photo: Pham Minh Thong

Photo: Pham Minh Thong

Recently, I was invited to visit the home and gallery of internationally-known Vietnamese artist Le Kinh Tai. After a ride through narrow streets and over one-lane metal bridges, we arrived at the artist’s home in Nha Be, a distant suburb of Ho Chi Minh City.

I was looking forward to seeing the work. Each visual artist has his or her own sensory language, just as poets and writers have their own verbal imagery. Cracking the visual code, so to speak, can be as exciting as understanding Chaucer in the original.

Upon arriving, I entered a huge three-story gallery whose plain white walls were covered with paintings of strange creatures. Under the unusual forms was a whole world of thought, emotion and perception to be absorbed and appreciated.

I spent the next hour carefully studying the paintings, looking for that elusive key to the artist’s soul. I first noticed what appeared to be a friendly lion done in hues of yellow and soft ochre. There was something familiar about it—not from Animal World; more like school and street celebrations for Tet. Then I noticed two words on the painting: K? Lân.

The k? lân is a traditional mythical animal, a composite of several real animals, and is the creature represented in the múa k? lân, what is commonly known in English as the ‘lion dance.’ A k? lân is supposed to bring good fortune, but almost hidden in the background of the painting were the words ‘I don’t care’ in English and some Vietnamese words having no meaning but echoing the sound of the English phrase. Stepping back for a better view, I noticed the splashes of red on the painting looked very much like blood. This was no friendly lion!

As I began to study other creatures on the walls with their big teeth, bulging eyes and elongated bodies, the artist’s use of the k? lân as a motif and metaphor was becoming clear. A young k? lân frolics in a sea of colour, a human child in the background. A large k? lân with a deceptive smile gathers followers, some seemingly inspired by his charisma, others following blindly, unthinking, and some with him for their own sinister purposes. How many people in the world want a leader to ‘save’ them rather than finding strength and meaning in their own souls?

On a large double canvas, a voracious k? lân has devoured human beings; their fragmented remains are enclosed in individual cells of the monster’s body, separated from the real world and from each other. Is it the portrait of a materialistic society? Does it represent a cold, machine-like economy? Or perhaps the hold of outmoded, stultifying traditions.

I asked the artist Le Kinh Tai about the variety of toothy grins ranging from friendly to sinister in many of his paintings. He replied somewhat sheepishly, ‘I only paint at night. First, I take a shower, go to my studio in my underwear and begin to paint. Sometimes I smile with gratitude for the good things in my life. Sometimes I grit my teeth in rage at all the needless suffering, poverty and blindness in the world.’

In artist Le Kinh Tai’s world, even the fish have teeth. Two striking paintings of wooden fish are found high on the walls. On one is written ‘Wooden Fish’ in both English and Vietnamese, and one warns ‘Stop eating, don’t touch.’ There are several folk tales related to people so desperate for food they carved wooden fish, dipped them in salt or fish sauce and pretended to eat them with their rice. One tale tells of a miserly teacher who fed his students only rice and a large salted wooden fish for his students to nibble on. They say he served the same fish for three years!

Today the term ‘wooden fish’ often refers to the ostentatious lifestyle of the nouveau riche who try to prove they are ‘better’ somehow by sporting luxury cars, homes and other symbols of wealth while frequently drowning in debt. Their hollow, materialistic lives do not satisfy. They are like wooden fish.

The Year of the Goat is celebrated in another of Le Kinh Tai’s large canvases. Is the goat smiling or leering? Its shifty eyes tell us to beware. The wealth of colours suggests a myriad of possibilities for the new year.

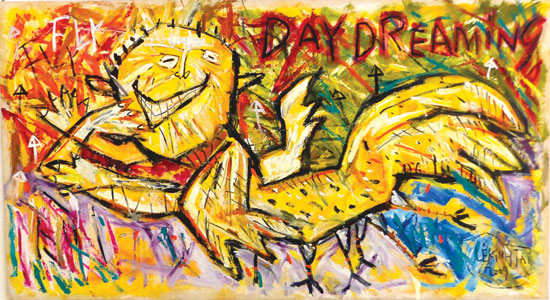

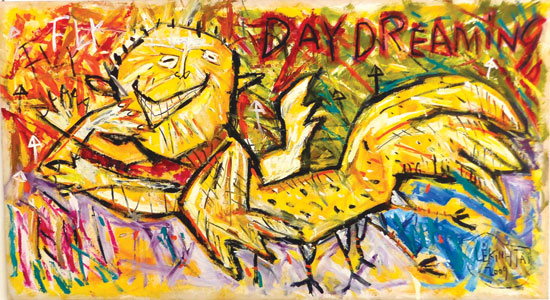

One of Le Kinh Tai’s most charming pieces is a painting of a six-legged chicken that is, in a sense, a self-portrait. The face has a happy, dreamy quality reminiscent of the artist’s own face and is called simply ‘Day-dreaming.’ In the corner of the painting is the word ‘Fly.’ The artist confessed he painted it after receiving an invitation to the 2009 International Artists’ workshop in the USA. Artists from fifty-six countries on five countries were given studios and a chance to paint for two months. One artist was then chosen to represent each continent. Le Kinh Tai’s works were chosen to represent Asia in the international exhibit.

When asked what artists or styles had influenced him the most, Le Kinh Tai mentioned two Vietnamese artists: Bui Xuan Phai, whose ‘ph? Phái’ (paintings of Hanoi streets) are world famous, and Tran Luu Hau, whose vivid use of colours is echoed in the artist’s own work.

One final piece that perhaps sums up something of the artist’s goals was a smaller painting. In it, the chicken has learned to fly. On its back are two children. It is appropriately titled ‘For my child.’

Le Kinh Tai’s paintings have a message relevant to both the present and the future that is specifically Vietnamese but with universal implications. Through irony and metaphors he speaks to the Vietnamese people.

I am sure I missed much of the meaning and symbolism in his paintings, but his passion for people, for children and the future of Vietnamese society is clear