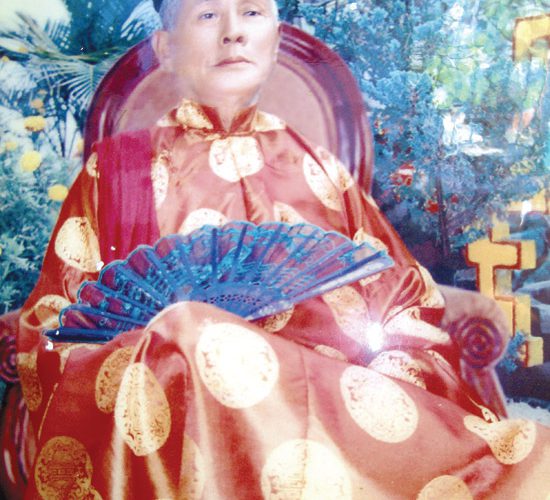

Mr Vo Van Toai, of Ly Son Island, Quang Ngai Province, is believed to be able to talk to spirits of the dead and call them to enter one-third-scale clay-and-wood statuettes.

When I asked when such a job had come into being in the area, the 70-year-old was quiet for a few moments as if trying to recall a story passed on by word of mouth.

About 200 years ago, King Gia Long gathered the youths of Ly Son Island to form a navy of 70 men, with five warships, led by Pham Quang Anh. Their job was to measure sea routes, explore fisheries and defend sovereignty.

One day, Pham Quang Anh and his ship, with 24 men, was lost in a storm. King Gia Long held a service in remembrance of the warriors and ordered a feng shui shaman to call their spirits home.

The shaman made 25 clay statuettes which he clothed and put in coffins. He put offerings beside the coffins, lit incense sticks and called the spirits to enter the statuettes.

The warriors’ descendants still make offerings on the death anniversary and clear up at a grave-visiting festival in April.

A wider custom of calling the spirits of the dead to enter clay statuettes began.

Mr Toai has worked as a shaman for more than 50 years. He doesn’t remember how many statuettes he has made.

Since the relatives of the dead believe the ‘skin’ of the statues must be pure, Mr Toai has to climb Gieng Tien Mountain, on Ly Son Island, to get clay grass does not grow on. Mr Toai has to use all the clay he gets from the mountain. If he drops any, it is dropping flesh or bone of the dead, which hurts the living spiritually.

A statuette is usually one-third-scale. It images many aspects of the human body, including the intestines, liver, anus and reproductive organ. Each organ must be made in accordance with the shape, colour, function and philosophy associated with it.

Mulberry-tree-trunks, which are no thicker than an arm, are used to make bones. Sections of mulberry branches go in the torso, seven for a man and nine for a woman, to symbolize the number of ribs. Silk threads are used for tendons.

Mr Toai said there was a rationale for the use of mulberry-tree-trunks in that the silkworm ate mulberry leaves, it became a butterfly, which produced new silkworms, which ate mulberry leaves, symbolizing changes in a lifetime and the philosophy of samsara, or eternal cycle of birth, suffering, death and rebirth.

A layer of chicken-egg yolk is applied all over the statuette, which gives the impression of skin.

Mr Toai performs a ritual, like the feng shui shaman of King Gia Long. The relatives, in a standing audience, usually cry. It takes 12 hours of formalities for the spirits to enter the statuette.

‘How do we know the spirits of the dead enter the statuettes?’ I asked.

Mr Toai said, ‘I can see them clearly. Usually, the spirit visits the relatives and friends before entering the statuette.’

Ly Son is 10 square kilometres and has 20,000 people, mostly living on fishing. The trade claims many lives and many bodies are not found.

While we were talking, a man came to ask Mr Toai to perform a ritual to worship his mother, who had just died. He also performs at funerals, does exorcisms (to drive out ghosts and devils) and drives away ‘ghosts that startle sleeping children’.

Most of the people on the island were very poor, Mr Toai said, and many of these poor people died because they couldn’t afford a big enough boat.

If a poor family lost a member and couldn’t find the body, they usually couldn’t afford a ceremony to call the soul. They went to a road intersection where the dead person had used to pass and collected soil to inter as if it were the body. There are thousands of such graves on Ly Son Island.

We came to a cemetery. Mr Toai said, ‘The graves look solemn but the only physical remains many of them contain are clay statuettes or some soil collected from a road intersection.’

Mr Toai looked around the cemetery with thoughtful eyes. I asked, ‘What worries you most?’ He said he had been worried that when he passed away nobody would take over the job of shaman. But the past few years his third, 42-year-old, son had been practising the same profession.