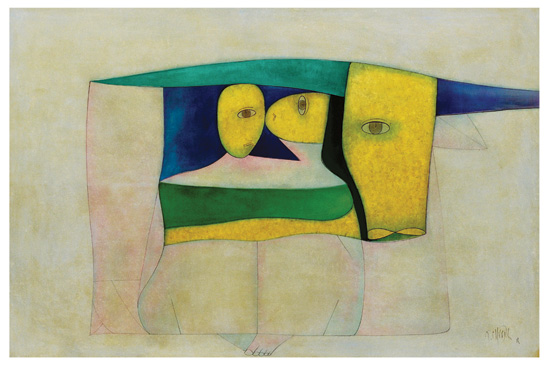

This artist uses only lines to create forms, and often geometry: circle, egg, rectangle, triangle, cube and free-running lines on flat surfaces. Thanh Chuong acknowledges an influence from Picasso, whose works he liked when he was still on the student benches. Joan Miró also, probably. Thanh Chuong is decisively influenced by modern art of the early 20th century in the West. He abandoned realism, went for cubism and modernized. He uses primary and gorgeous colours in sharp contrast and decoratively, in the manner of Matisse and the Fauves.

With intelligence and character, he has digested Westerm modern art quickly and smoothly, creating brand Thanh Chuong, Vietnam. The paintings are said by many to be Vietnamese. I would say they are from modernity and identify with ‘new Vietnamese folklore’.

I see buffalo boys, kites, conical hats, the moon, self-portraits, lattices of spontaneous cubist compositions, faces up-turned toward the sky, or in hide-and-seek, or inclined heads much like in Vietnamese folklore, with stylized convention as in many wood-relief figures in ancient Vietnamese communal houses. Due to limitations of the boards the craftsmen of the corporations used they had to shorten or stretch figures and these are burlesque and full of life. Folk art of Vietnam is sometimes frolicsome, with tilting and slanting people at play. Chuong’s renditions can be lotus-pink, crimson, peach-red, banana-leaf green, kingfisher blue, gold and canary, colours frequently avoided by oil painters but usually seen in the costumes and decorations in festivals of rural Vietnam, in the three-layered and seven-layered tunics of women, many-splendoured and swinging. In the eyes of the peasants, beauty is shown in terms of differences.

On bridging the art of Vietnam, rich in folklore, with modern world art, we must mention the renowned pioneer Nguyen Tu Nghiem, who has exploited the motifs of ancient Vietnamese art, from the bronze drums of the Dong Son culture to the carvings and sculptures of village communal houses in the 17th century, and transformed them into contemporary language. His paintings, including Ancient Dance, The Bamboo-Hero of Zong and The Immortal, are full of a spirit of majesty, quietude, sublimation in spiritual life and religion. Thanh Chuong, by contrast, refers to everyday rural life, with the flavour of children’s folksongs, merry and buoyant carnivals and an eye for new shapes, funny and imaginative, rich in modern decorativeness.

Thanh Chuong is afflicted with a number of ills endemic to folk art – such as being easygoing, relaxed, plain, bare, comic – that may lead to superficiality. Thanh Chuong produces in great quantity. It seems ideas and drawings flow too rapidly for his control. With a flexible mind, he need not repeat himself but, due to his method, too quick and too often, his paintings can give an impression of déjà vu and can be boring.

The paintings are nevertheless still hot, best-selling. They appear to conform to the requirement of eye-pleasing decoration for a public tired of industrialization, with unsophisticated taste. Or is it a public bored and insensitive to postmodern culture and with a nostalgia for the golden age of modern art? May it be a thirst for the freshness of the rustic landscape deeply buried in the memory of the childhood of humankind? In recent years in expression generally there has been a gargantuan return to the village with buffaloes, cows, comic hats, the joy of folksongs and the naive of this period of time.

Notwithstanding, Thanh Chuong’s works do cause a great number of outbreaks of ideas in public opinion. In the International Year of Volunteers, 2010, they were selected by the United Nations as a symbol and printed on it stamps.